The Seas & Us

A Paddler's Adventures & How We Can Stop Harming the Ocean

by Doug Simpson

I first started paddling kayaks when I was eight years old. My family had rented a small cabin for the summer on an island near Vancouver. Our neighbour, old Mrs. Sweeney, had two kayaks that she let me use, as long as I stayed within her sight. That was the deal, anyway, but she was near sighted and forgetful and I had more freedom to roam than she imagined. Or maybe she understood that all along and it was I who was fooled.

The kayaks had canvas skins wrapped around wood frames. When you eased into one you heard creaking sounds of wood on wood. The frame seemed like the skeleton of an animal and when it moved within the skin the whole boat came to life. I imagined I was riding some big sea mammal, following the fish and whales to far off lands. The boats moved through the water with very little effort. There was no bashing of waves against hard fiberglass or wood. Just a gentle cleaving of the water as the skin absorbed some of the energy of the sea. This was the intention of the early Inuit who developed and used these boats for their survival. They needed a stealth boat. At the time I thought that these kayaks were original Eskimo hunting kayaks. Maybe I imagined this or maybe somebody put me on. Years later I learned that they were wood and canvas kit boats from England. But I was hooked early on.

During my university years I spent summers in the Canadian Arctic, working for gippo mining exploration companies. If we found some obscure deposit our company would exaggerate and publicize the find in order to run up its share price. Things were wild in the Vancouver stock market back then. Most of the areas that we worked in had been scoured flat by glaciers that had weighed heavily on the land, forming a vast peneplane. The country has almost as much water, in the form of disconnected lakes, as land. We needed a transportable boat. It was during the long days of Arctic summer that I started thinking about folding kayak designs.

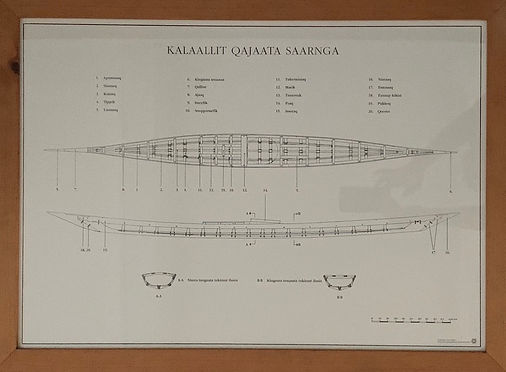

The first crude kayaks that were made by Aleuts in the Bering Strait area over 4,000 years ago were likely used just to recover seals, otters or birds speared from shore. Over time hunting kayaks were developed and their use spread across the Arctic as far as Greenland. The Aleuts and Inuits developed sophisticated models designed for various hunting tasks in different conditions and environments. Some of the very best, most beautiful designs were made in West Greenland: long, narrow, low and fast. The earliest commercial fiberglass sea kayaks were modeled after one of these remarkable crafts in the 1970's.

Folding kayaks were developed in the early 1900's. These had heavy wood frames with canvas and rubber skins, were designed for river use, and were considerably shorter and wider than the sleek Greenland boats. My interest was in the sea kayaks. I studied the drawings of Greenland kayaks and was also influenced by the burgeoning development of fiberglass sea kayaks in Britain and North America. Instead of wood I chose aluminum magnesium aircraft tubing for my framework. I had learned a little about the tubing during pilot training I had undertaken in Edmonton, Alberta. I received my first patent on the kayak design in 1977 and began making Feathercraft folding kayaks with my new partner, Larry Zecchel, in 1979, on Granville Island, Vancouver. Although the skins of our kayaks were made of rubberized nylon and later welded urethane-coated nylon, they have always shared the performance characteristics of the early Greenland boats: unlike fiberglass they are silent on the water and paddlers feel the gentle flex of frame and skin gives them a more intimate feeling for the water. Many people experience a lightness of being unattainable in any other craft.

Our timing was good and sea kayaking was starting to take off. Feathercraft Kayaks were the first folding kayaks to be designed specifically for sea touring and they became the standard by which other brands were judged. By 1990 we had a staff of about 20 and were selling our premium folding kayaks all over the world. Our main markets were in North America, Europe and Japan. We continued to make our boats and accessories on Granville Island until we shut down in 2017.

Even before we made our first kayak we had started exploring our local coast in cheap fiberglass river kayaks. We didn't know much. The journey we took across the Strait of Georgia, across its shipping lanes in dense fog was just plain stupid.

At first we limited our paddling to the local Gulf Islands or the myriad islands just to their north between Vancouver Island and the mainland. We learned our sea lessons slowly, by osmosis. That is the best way. When we later started going to the outer coast we at least knew how to handle our kayaks and set up camp.

The eventual success of the boat business led to a problem for us: we had no time in the summer to go paddling! This led to winter paddling trips and it was during these that we really sharpened our ocean paddling skills. The seas off the west coast of B.C. are relatively benign during the summer months. In winter the Pacific High, which dominates in summer, retreats with the sun and is replaced by large low pressure systems that blow in from the Pacific. Storm winds exceeding 40 to 60 knots are not uncommon. Even hurricane force winds occur occasionally. We spent a lot of time huddled under tarps, sheltered in the forest, in the rain. Learning when to go, and when not to go became key for survival, as did paddling in challenging conditions when we eventually did set off. We rationalized this extravagance on the assumption that the kayaks we were designing and making would become stronger and more seaworthy. And they did. It was lessons learned on these crazy trips that prepared us for paddling in exotic places far from our own coast.

In this work I describe my early paddles along my local coast as I slowly began to realize the effects of humankind's massive assault on the oceans. I describe how clear cut logging and over-fishing affect the health of salmon runs. Following a chapter on our attempted Bering Strait crossing there is an outline of how indigenous people migrated from Asia across the strait and down the Americas, and why their successful maritime culture has long been underestimated by westerners. Chapters on the fishing business are followed by an expedition around Cape Horn where we found a surprising lack of fish. A chapter on sea level rise is followed by paddling trips to West and East Greenland where the ice cap is melting faster than scientists predicted even five years ago. During a crazy adventure in French Polynesia and journeys in the Bahamas and the Okinawan archipelago I witnessed the desolation of coral loss and the scourge of plastic in the near shore and on beaches. I sat through two category 4 typhoons while my partners and I were trying to paddle and sail our kayaks from Japan to Taiwan, grounded by these increasingly intense storms.

There are many things we can do to prevent and in some cases even reverse the worst effects that we have caused. I outline why we must control the great industrial fishing operations that span the globe and also protect 30% of the oceans from fishing and resource extraction. I describe how my home province of B.C. is actually a leader in plastic recycling and how this knowledge could be useful in third world countries. Ocean warming and acidification are two of the most intractable changes that we face and yet there are still things we can do to limit their effects. If we act now.

I have relished my journeys on the ocean but often understood little of the harm that I and the rest of humanity, especially in industrialized countries, have inflicted on it. This must change. Hopefully, you will enjoy some of the adventures that a few friends and I have been lucky enough to experience over the past forty years. You will also learn of the threats that all marine life faces. I've included suggestions on how we can repair our relationship to the planet's diminished oceans. But we cannot wait. More than anything, this book is a call to action.

Today millions of youth all over the world are demanding meaningful change. We must listen, and act. When I started writing this only a small minority of people were alarmed about the climate emergency and even fewer had concerns about the damage to life in the oceans that our actions are causing. Even now most of the talk is about issues on land. And there is still precious little action. The vast seas that cover 70% of earth sustain us. If we truly understand this we can start to heal this blue, watery orb we all call home. Because we can and we must.

Some of the locations mentioned have been indicated in decimal degrees of latitude and longitude. You can plug these into Google Maps or Google Earth to follow along.